(adapted from the introduction to Planting Red Geraniums: Discovered Poems of James Hearst)

In his 1977 poem “Surprise,” James Hearst writes of friends who attempted to convert their garage into a mushroom garden. Despite their efforts, the mushrooms did not grow, so they shoveled out their experiment and dumped it in their backyard. Hearst concludes the poem, “… After the first / warm June rain the lawn mushroomed / with mushrooms.”

Like the gardeners who reaped an accidental harvest, I found myself the beneficiary of an unexpected find made when developing the James Hearst Digital Archive. During a research visit to the University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections, I unearthed some handwritten drafts and typed worksheets of Hearst’s published works that were tucked away in folders. As I was scanning files to include in the digital archive, comparing pages with published poems, I found some untitled worksheets that I couldn’t initially match with the corresponding published poems. Then, in one of those rare, lightbulb-going-off-over-my-head moments that really do sometimes happen, I realized that some of the drafts were for poems that had never been published.

This discovery was a shock to me because of the exquisitely detailed bibliographic work that had already been done on the writings of James Hearst. Both Robert Ward (author of James Hearst: A Bibliography of His Work) and Scott Cawelti (editor of The Complete Poetry of James Hearst) devoted years of effort to tracking down, documenting and republishing Hearst’s work. Additionally, James Hearst and his wife, Meryl Norton Hearst, had kept painstakingly accurate records of Hearst’s published poems. Without all of this to build upon, it would have been impossible to envision even attempting to create the James Hearst Digital Archive.

From available records, it appears that Hearst was first contacted by the University of Iowa Libraries in 1945. In 1950, he contributed materials for a collection focused on Iowa authors along with a self-effacing cover letter that noted some worksheets he had found while “rummaging” and suggested that if an included sketch seemed inappropriate, she could throw it away. Over the years, Hearst added some correspondence (to a collection now called the James Hearst Papers), but Robert Ward did not seem to be aware of these materials when, thirty years later, he did bibliographic work on Hearst. James Hearst’s literary estate was later donated to the University of Northern Iowa, and the majority of his papers are housed in the UNI Rod Library Special Collections & University Archives.

Planting Red Geraniums draws primarily from materials in the James Hearst Papers, and I believe that it offers a significant supplement to the canon of Hearst’s poetry. This collection is not a representative cross-section of his verse. Rather, in the aggregate it provides intriguing insights into Hearst’s creative process.

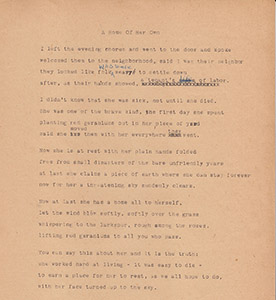

For example, two poems (“A Home of Her Own” [left] and “The Land Owner”) share some language but offer distinctly different approaches to the story of a neighbor who spent her last years living near Hearst. This is the same subject as that of the poem in Hearst’s 1951 collection, Man and His Field, “For a Neighbor Woman.” That memorable poem that chronicles the day when this neighbor passed away (thanks to Jeremy Schraffenberger for first making this connection). Hearst approached the same subject in the “A Home of Her Own” and “The Land Owner,” but in those poems he emphasized his initial meeting with this neighbor. Though aware of the hard life she had led on a small, rural farm, he was also struck by her tenacity, and both poems repeat the image of the red geraniums (from which the new volume takes its title) that she had brought with her and transplanted to her new surroundings. I imagine that Hearst could not help but identify with someone who had left the challenging but rewarding work of a farm for the greater comforts of suburban life, keeping with her a vivid sign of the beauty she had cultivated amid trying conditions and still wished to preserve.

For example, two poems (“A Home of Her Own” [left] and “The Land Owner”) share some language but offer distinctly different approaches to the story of a neighbor who spent her last years living near Hearst. This is the same subject as that of the poem in Hearst’s 1951 collection, Man and His Field, “For a Neighbor Woman.” That memorable poem that chronicles the day when this neighbor passed away (thanks to Jeremy Schraffenberger for first making this connection). Hearst approached the same subject in the “A Home of Her Own” and “The Land Owner,” but in those poems he emphasized his initial meeting with this neighbor. Though aware of the hard life she had led on a small, rural farm, he was also struck by her tenacity, and both poems repeat the image of the red geraniums (from which the new volume takes its title) that she had brought with her and transplanted to her new surroundings. I imagine that Hearst could not help but identify with someone who had left the challenging but rewarding work of a farm for the greater comforts of suburban life, keeping with her a vivid sign of the beauty she had cultivated amid trying conditions and still wished to preserve.

In writing three different poems about the same topic, Hearst provides insight into his creative process. He often circled his subjects, spiraling in on the significance of a specific work. This is particularly apparent in the poems from the collection that were discovered in a folder that Hearst had marked as “rough drafts.” It can be a fraught editorial decision to include unfinished work in a published collection, and the choice to do so in this case was not made lightly. But these “rough drafts” were not abandoned works, and nine of the poems from that folder were eventually published during Hearst’s lifetime. The remaining drafts, which are published in Planting Red Geraniums for the first time, were typed and often included handwritten additions and deletions.

Some of these drafts are less concise than many of Hearst’s published works, testifying to a composition process in which he tried out language like seeds dropped into the ground, cultivating and pruning, then allowing the finest words to be harvested. In fact, these poems suggest that he subscribed to the philosophy of his friend and contemporary Robert Frost, who said that poems should “say the most they can in the fewest words possible” (an exhibit in the James Hearst Digital Archive that explores multiple drafts of the poem “Three Old Horses” examines this issue in more detail). These pieces provide a unique in-process view of Hearst as a writer. At the same time, some of these poems—particularly “Spring Weather” and “Survival”— are as accomplished as any other work Hearst published during his career.

Some of these drafts are less concise than many of Hearst’s published works, testifying to a composition process in which he tried out language like seeds dropped into the ground, cultivating and pruning, then allowing the finest words to be harvested. In fact, these poems suggest that he subscribed to the philosophy of his friend and contemporary Robert Frost, who said that poems should “say the most they can in the fewest words possible” (an exhibit in the James Hearst Digital Archive that explores multiple drafts of the poem “Three Old Horses” examines this issue in more detail). These pieces provide a unique in-process view of Hearst as a writer. At the same time, some of these poems—particularly “Spring Weather” and “Survival”— are as accomplished as any other work Hearst published during his career.

And, of course, this may not be the end. Could there be more James Hearst poems out there, tucked away in folders or published in obscure magazines? Absolutely. There may be more poems, more interpretations, and I am optimistic that there will be new readers of James Hearst’s poetry. James Hearst still remains an active part of our literary community, and it is my hope that the poems in this collection, poems that have surprisingly mushroomed into existence, will preserve, extend and enrich our understanding of James Hearst’s poetic legacy.

— Jim O’Loughlin

Contents

"Whispering to the Larkspur": Unpublished poems considered for Man and his Field

"Triumph in the Autumn": Drafts

[Thank goodness it doesn't bug you often]

"The Truck in My Mind": Uncollected Poems