Note: This exhibit is based on a presentation by Scott Cawelti at the James and Meryl Norton Hearst Center for the Arts (in James Hearst's former home) in Summer 2014.

My introduction to James Hearst’s poetry came in the form of music: "Blind With Rainbows," an epic-like poem he published in 1962 as a cantata for the opening of Russell Hall—SCI’s brand new music building. Bill Latham wrote the music, Hearst the lyrics. 52 years ago.

I found it unforgettable, both as music and as poetry. In it, Hearst celebrated creativity, not just self-expression, but the difficulty of self-expression:

His road is hard who bears within himself seeds of

sun, who sees how patient earth cracks and strains to

bring a flower to bloom, how apple buds are mauled by

the tiger growth into their ripened fruit, how forcing

sap shoulders its way when April stirs the trees, how we

are born in pain and feel the scar all our lives who carve

stones from our hearts.

So for me these Hearst cantata lyrics preceded any knowledge of his poetry for me.

My next experience came in the form of a few well-known poems that people seem to know and mention: “How the devil should I know if there are rocks in your field,” from “Truth” and “You said take a few dry sticks, cut the ends slantwise to let in water—“ from “Forsythia”—both poems that seemed song-like to me.

Then I met James Hearst, first as a teacher for a graduate class, right in this very spot, one floor down, then as a colleague, and admired him mostly from afar, since I was young and preoccupied with—well, everything.

Then I met James Hearst, first as a teacher for a graduate class, right in this very spot, one floor down, then as a colleague, and admired him mostly from afar, since I was young and preoccupied with—well, everything.

Only later when I began editing the poems in the late 1990s for the complete poems anthology did I really began to pay attention to his large body of poetic work—over 600 poems from the 1920s until his death in 1983.

After my retirement in 2008 I returned to his poetry as a musician, which was in fact my first profession before I discovered I didn’t like rehearsing all that much. Years ago I had written music for Hearst’s 1937 poem “The Movers” and more or less performed it a few times, not very well. But after 2008 I returned to it, knowing I had a start. And it just unfolded, more or less naturally (at least some of it.)

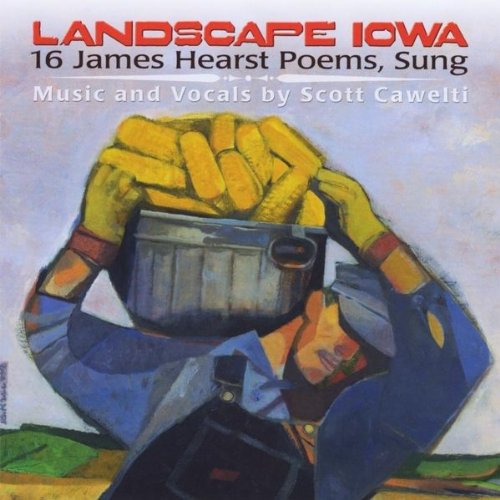

Then came “Truth,” “Forsythia” and 13 others, and before long I had a CDs worth of Hearst poems as songs, recorded them at Catamount studios and have been performing them ever since as a Humanities Iowa scholar. It was great fun, and the songs/poems seemed to reach at least those familiar with Hearst’s poetry.

Now, with this opportunity to reflect further on James Hearst’s poetry as potential songs, in the last month I’ve found three more poems that work as songs—I think—and many more that don’t. Which raises the question: What’s the difference? Why do some poems almost write themselves as songs, and some don’t?

What is poetry? The definition I like is "weighted language." The more weight words get from a writer/poet, the more we read it like poetry—that is, slowly, paying attention to the words and meaning

s, since they’re clearly not meant to be read quickly, just for fun or information. Most prose is in fact not weighted—we read quickly, right through the words to their meanings and take instruction, get the story, change our behavior, and so on.

But poetry—weighted language—requires attention:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Tell all the truth, but tell it slant.

No one who lives here knows how to tell a stranger what it’s like, the land I mean. . .

Now, language can be weighted many ways: with rhyme, rhythms, word choice, metaphors, imagery, story, and all the poetic devices we learned in introductory poetry classes. When a poet works more with rhythms and rhymes to weight language, a song looms. Not always, but it’s a start. Repeated lines help, as do surprises, which music can help emphasize.

Now, to demonstrate, here are six James Hearst poems. I've set three of them to music [click on play arrows to listen], but I didn't feel the other three would work. Read them and see if you agree.

“I’m a Christian but...” "No Answer"

"Chill Comfort" "This Is How They Do It"

"Day After Day" "Where Did They Go?"

— Scott Cawelti