The Versions of "Three Old Horses"

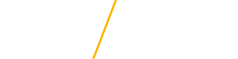

When the poem “Three Old Horses” was published in Man and His Field (1950), its focus on the daily experiences of a farmer was not thematically unusual for the farmer-poet James Hearst. However, it was atypical for Hearst to use a triplet rhyme scheme with stanzas of three rhyming lines (one for each horse, it seems). More significantly, there are also three worksheet drafts of this poem to be found in the James Hearst Papers at the University of Iowa. These drafts provide unique insights into Hearst’s process of revision, showing both his care with word choice and his efforts to pare down unnecessary language. However, the different stages his poem went through not only illustrate the linguistic aspects of revision; they also reveal how Hearst struggled to represent his own ambivalence toward the rise of mechanized farming.

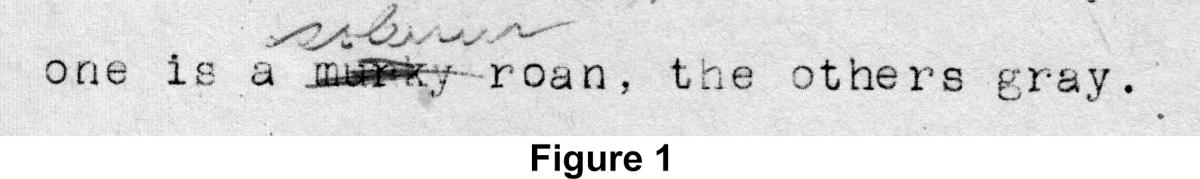

Starting small, one can notice certain changes in word selection. In Figure 1 (from version A of the poem), Hearst makes a handwritten adjustment, changing a “murky” roan to a “solemn” roan. While the word “murky,” could be interpreted as somber, it would most likely be read as a description of a dirty or muddy color. Hearst opted instead for “solemn” giving a more emotive attribute to the animal.

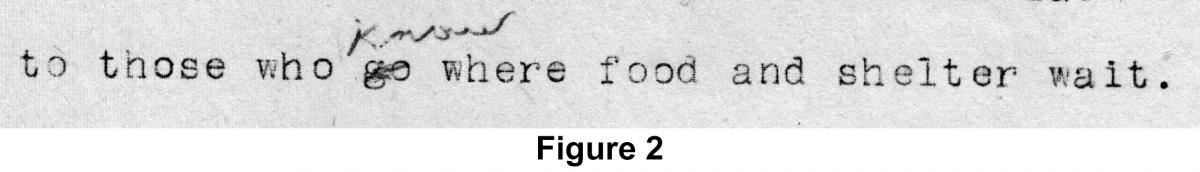

Likewise, in Figure 2 (also from version A), Hearst changes the meaning of the line when describing why the narrator and the horses are walking together by simply alternating “go” to “know.” This s ubtle shift gives both the horses and the narrator the same level of consciousness, personifying the horses further.

ubtle shift gives both the horses and the narrator the same level of consciousness, personifying the horses further.

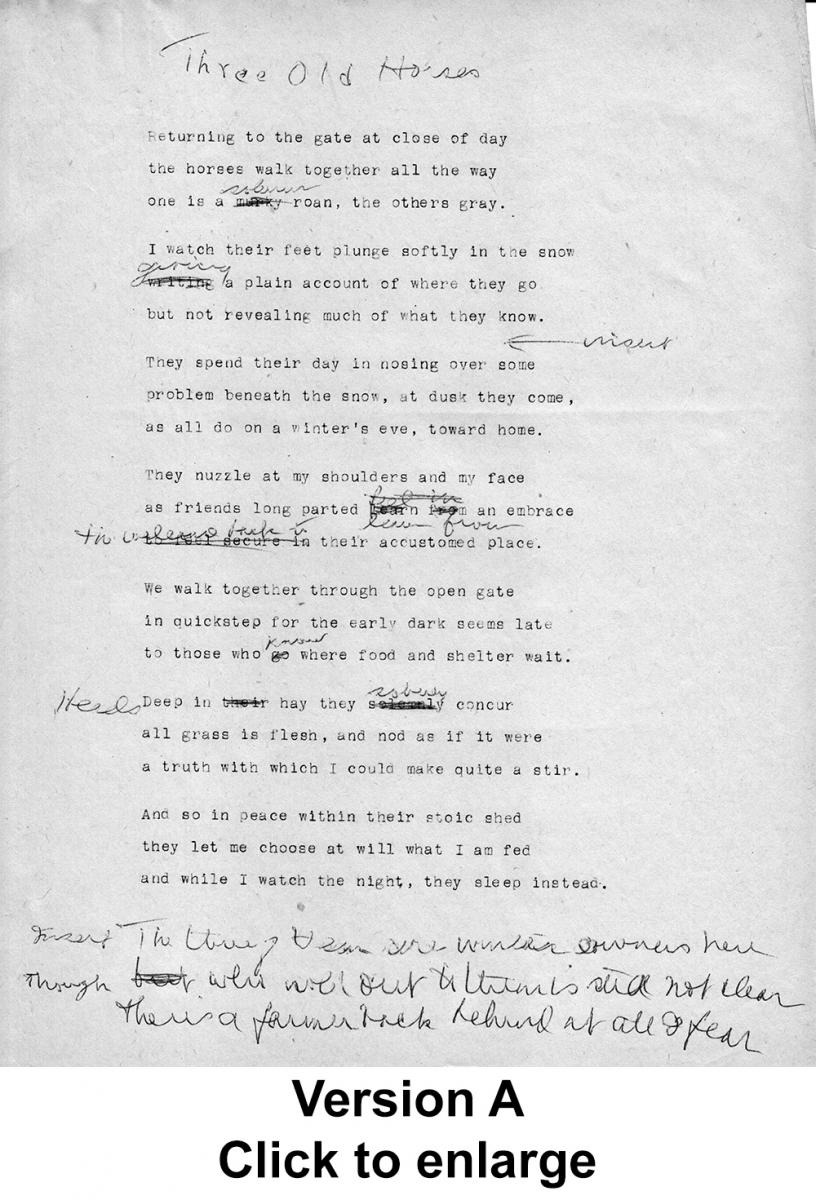

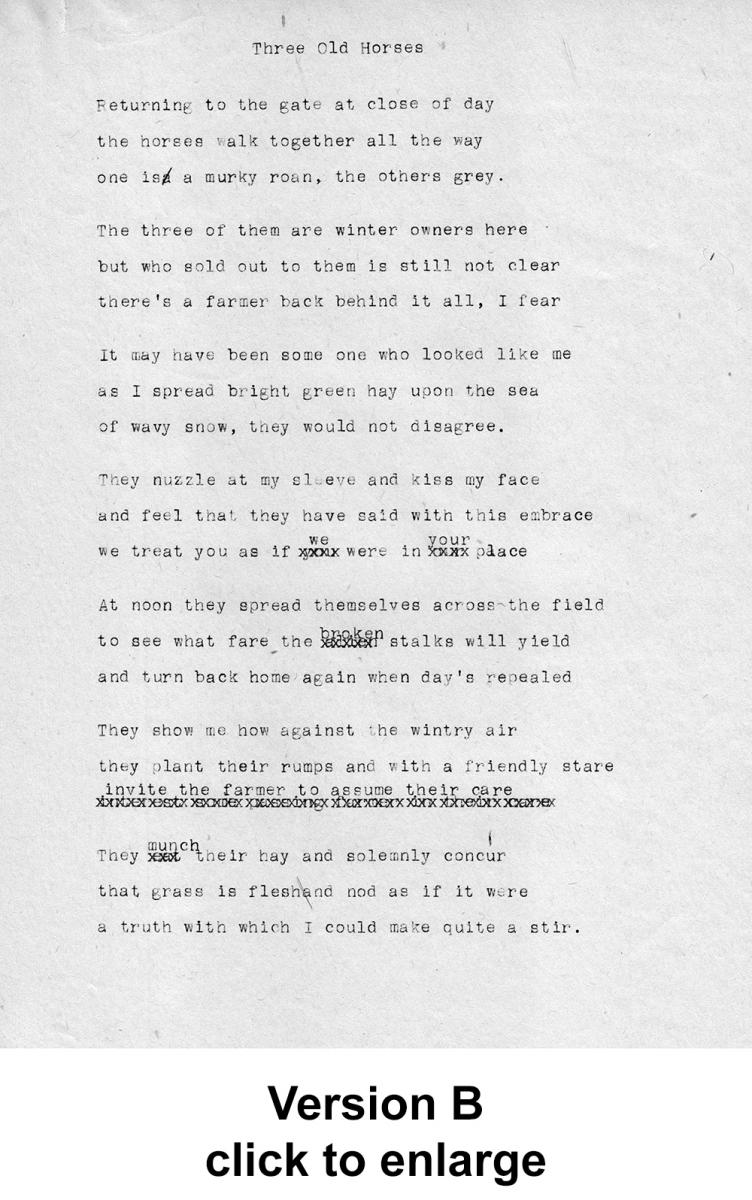

Version B of the poem (which was likely composed later because version A has a handwritten title) while thematically similar retains only three stanzas from version A, cutting four stanzas and adding four new ones. There is no surprise in a revision working that way. What is unusual is that version C (the version which was published) does not only alter version B, it also returns to version A and reincorporates four A stanzas that had been removed from B.

way. What is unusual is that version C (the version which was published) does not only alter version B, it also returns to version A and reincorporates four A stanzas that had been removed from B.

Throughout all of these changes, the subject of the poem, three horses and a farmer’s connection to them, remains the same, despite the absence of certain passages. However, these forgotten passages are worth considering because they speak to concepts that Hearst initially wanted to put in words before he managed to do so in a more concise manner.

Consider the following verse from version C, the published version of the poem, which says of the horses:

The three of them are winter owners here

but who sold out to them is still not clear

there’s a farmer back behind it all, I fear.

In Version B, this stanza is initially followed by a passage that was later omitted:

It may have been someone who looked like me

as I spread bright green hay upon the sea

of wavy snow, they would not disagree.

Both stanzas speak of farmers selling their horses, and with the second stanza in version B, Hearst makes his guilt explicit by suggesting he was the farmer to blame. However, in the final version, Hearst does not include this stanza, which allows the poem to be less confessional and broader in its claims.

Apart from this omitted passage, other two verses in Version B were also not included in the final version.

At noon they spread themselves across the field

to see what fare the broken stalks will yield

and turn back home again when day’s repealed

They show me how against the wintry air

they plant their rumps and with a friendly stare

invite the farmer to assume their care.

There is nothing incorrect about these stanzas. In fact, the meaning behind them is still conferred in the final version, only with different passages. Hearst still speaks of how the horses spend their day in the fourth verse of version C, and how they return home at dusk to their farmer’s care during the winter, “where food and shelter wait,” in the sixth verse. But their removal has allowed Hearst to take his personal experience and apply it more broadly.

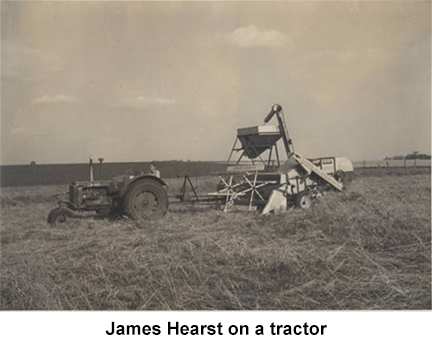

With these drafts, Hearst has also left traces that can be used to understand his thematic concerns. For instance, the passage omitted from version B that attests to Hearst’s guilt for selling the horses can be compared to another of his works. Hearst dedicated five essays to the relationship between horses and men in his book Time Like a Furrow: Essays (State Historical Society of Iowa 1981). In his essay “Horse Power,” Hearst expresses guilt for trading their last work horses in exchange for a tractor after he and his brother took over the farm. He describes his relationship with the horses in the farm as a loving one—they named all their horses and often played with them. When they sold off some of their horses, Hearst felt like a traitor for having “sold [his] friends into slavery.” In his essay, Hearst speaks directly to his personal experience. When drafting his poem "Three Old Horses," however, he excised his personal experience, resulting in the final version that reads, “who sold out to them is still not clear - there’s farmer back behind it all, I fear.”

With these drafts, Hearst has also left traces that can be used to understand his thematic concerns. For instance, the passage omitted from version B that attests to Hearst’s guilt for selling the horses can be compared to another of his works. Hearst dedicated five essays to the relationship between horses and men in his book Time Like a Furrow: Essays (State Historical Society of Iowa 1981). In his essay “Horse Power,” Hearst expresses guilt for trading their last work horses in exchange for a tractor after he and his brother took over the farm. He describes his relationship with the horses in the farm as a loving one—they named all their horses and often played with them. When they sold off some of their horses, Hearst felt like a traitor for having “sold [his] friends into slavery.” In his essay, Hearst speaks directly to his personal experience. When drafting his poem "Three Old Horses," however, he excised his personal experience, resulting in the final version that reads, “who sold out to them is still not clear - there’s farmer back behind it all, I fear.”

In "Three Old Horses," Hearst conveys his love for horses, describes his relationship with them as a farmer and friend, and offers a glimpse into his own feelings of guilt. A closer look into the two earlier drafts of this poem allows for a deeper understanding of Hearst’s creative process. More specifically, it allows readers to appreciate how meticulous he was when selecting certain words during the first stages of drafting his poems and how persistent he was in retaining the feelings that inspired him to draft the poem in the first place.

Works Cited

Hearst, James. “Horse Power.” Time Like a Furrow: Essays. Iowa State Historical Dept., Division of the States Historical Society, June 1981.

---. Man and His Field. Allan Swallow, 1951.

— Polly Alfano

Permission to reproduce drafts of "Three Old Horses" has been granted by the Special Collections Department of the University of Iowa Libraries, where the original versions of these drafts can be found as part of the James Hearst Papers