James Hearst: Poet and Friend

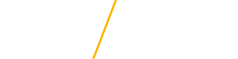

George Day (1926-2022) taught in the UNI Department of English (now part of the Department of Languages & Literatures) from 1967 to 1994. He was a colleague of James Hearst's and offered classes in American literature. He had a special interest in Western American literature. This exhibit is based on a presentation by George Day at the Hearst Center for the Arts in Summer 2014.

I did not know James Hearst for very many years—only about fifteen. Our friendship was no doubt shorter than that of other people here today.

As I planned/thought about this talk, I recalled Jim’s theory (or secret as he called it) of teaching. I think it applies to public speaking as well as classroom teaching. I may have to make use of it today. When Dr. Bill Reninger first asked Jim to come into town to teach a class at the college, Jim hesitated. He felt inadequate to the task. He had no college degree, had never taken any education courses, and had never taught anything. But he agreed to give it a try and, after a few class sessions, he felt comfortable. For he had discovered, he said, the secret of successful teaching: you take the ten or fifteen minutes worth of knowledge about your subject that you possess and…stretch it out to fill a two hour class period. And you have it made.

As I planned/thought about this talk, I recalled Jim’s theory (or secret as he called it) of teaching. I think it applies to public speaking as well as classroom teaching. I may have to make use of it today. When Dr. Bill Reninger first asked Jim to come into town to teach a class at the college, Jim hesitated. He felt inadequate to the task. He had no college degree, had never taken any education courses, and had never taught anything. But he agreed to give it a try and, after a few class sessions, he felt comfortable. For he had discovered, he said, the secret of successful teaching: you take the ten or fifteen minutes worth of knowledge about your subject that you possess and…stretch it out to fill a two hour class period. And you have it made.

My friendship with Jim was rich and in retrospect seems longer than it actually was. We had many a great conversation in this very house (and often in front of the fireplace, which has been so carefully preserved by the entrance). I was a guest here several times for meals, and Jim and Meryl were guests in our home a few times. Jim and I belonged to the Supper Club together, and his English department office was just a few doors away from mine. In addition, I have a file of notes and letters that Jim sent to me on several occasions.

So, although I do not claim to have been a close friend, I consider our friendship a good one with some depth. Of course, I must remind you that my recollections are just those of myself, just one point of view. I think I have a fair understanding of his character and personality, but probably no one knew or understood James Hearst completely. He was a complex and highly intelligent individual who had gone through fire and kept most of his suffering to himself.

But for me, Jim was a friendly man. He was easy to like, and as a result he had many, many friends and I been one of them. It is not too much to say that he had a magnetic personality. I am sure he would scoff at that adjective. Yes I would go further and say he was, or could be, as the occasion required, quite charming. Especially, need I add, in the presence of women. Jim was born with, I believe that wonderfully engaging ability (and it is rare) to listen carefully and with sincere interest to whatever the other person was saying.

But for me, Jim was a friendly man. He was easy to like, and as a result he had many, many friends and I been one of them. It is not too much to say that he had a magnetic personality. I am sure he would scoff at that adjective. Yes I would go further and say he was, or could be, as the occasion required, quite charming. Especially, need I add, in the presence of women. Jim was born with, I believe that wonderfully engaging ability (and it is rare) to listen carefully and with sincere interest to whatever the other person was saying.

Jim was never aloof or stand-offish. He never played a role—the creative genius, the aloof poet. He was always who he was, James Hearst, a dirt farmer who also wrote poetry. He said it was not the job of a poet to advertise himself, it was to write poems. As the young people today would say: “He was the real deal.”

In conversation and in his autobiography, the names of his many friendships is legion. This is particularly true of his many sojourns in hospitals—Mayo Clinic , U of Iowa—where doctors, nurses, therapists, and orderlies quickly became attached to this patient. Lifetime friendships often developed. Another indication of how Jim attracted people was the abundance of people who readily stepped forward to give Jim a helping hand over the years. People, total strangers included, always seem to “love” helping Jim.

"James Hearst" by Paul Engle

I walk around

with a map of Black Hawk County, Iowa,

in my hands.

That old chief, Black Hawk,

full of dignity and daring,

loving his land more than his life,

after his capture went to Washington, D.C.,

and said to the President of the United States;

“You are a man. I am a man.”

He never lived in the County of his name.

But Jim Hearst is there,

a tough and gentle man,

tongue like a tomahawk

splitting your skull with his wit,

then easing it with a blast of bourbon.

On a clear day you can see him

plow the long fields and the lyrical English language

along the banks of the unblue Cedar River.

This farmer knows

the lines of a Black Angus steer,

the lines of a Hampshire hog,

the lines of his own nourishing poem.

With his broken back,

the tensile strength of his will,

he backs the brutal beauty

of men and women walking together

in the flaming August noon,

in the frozen December day,

in the dark light of eternity.

He hates self-pity,

as he hates hate.

He wipes sweat from his face with a quick hand.

He caresses the yielding snow with a shaking hand.

He knows that men, women, children

are horrible and holy.

All his years he lived a double life:

in the world of the living poem,

in the world of the living pain.

He savors jokes with joy,

tasting them on his tongue

as if they were hickory-smoked

over a slow fire.

Heart of a bull,

hand of a hawk,

ear of a dog,

eye of a cat,

Jim Hearst, you old Indian,

you old bastard,

burned in the bold air above you

in Black Hawk County

are the proudest words we can speak:

Here is a man.

Let the earth be lucky.

A unique aspect of Jim Hearst’s personality was his intense interest in people who at some point in their life changed jobs or occupations/professions. This was something Jim and I had in common. Jim had worked on and then managed his family’s farm before becoming a poet and a teacher. I had worked for and then managed my family’s building supply business. This fact may have been the original basis for our friendship. Jim seemed fascinated by such a dramatic change of lifestyles and similarly I was interested in his story. He quizzed me about it often and even sometimes would make the outrageous claim that he and I were the only ones in that English department who had ever done a day’s work. Not literally true at all, of course, and it could be a bit embarrassing, but music to my ears nevertheless. Such flattery from Iowa’s most famous poet!

Jim had a keen interest in many areas that some would regard as mundane, certainly they were non-poetic or aesthetic. Here are two memorable examples:

Sometime in, I believe the 1980s, the fourth floor of the UNI Library was completed and opened up a large new area for additional stacks and offices. A dedication ceremony was planned and the novelist and poet Frederick Manfred was invited to give the dedicatory address. Manfred was a friend of mine and I had the good fortune to be his guide while he was in Cedar Falls. I had long thought the two writers, Hearst and Manfred, should meet and so I was able to set up a time when that could happen. I was sure that out of such a meeting would come an illuminating exchange of ideas about literature and their own writing. I did note, however, that in anticipation of their meeting Jim seemed to be more interested in the legendary large and beat up old Cadillac that Manfred was famous for driving all over the country. After his speech at the library, Manfred and I drove down Seerley to this house. (I of course had remembered to bring a pen and paper so I could capture important bits of their conversation. The first part of their immortal conversation went like this:

Sometime in, I believe the 1980s, the fourth floor of the UNI Library was completed and opened up a large new area for additional stacks and offices. A dedication ceremony was planned and the novelist and poet Frederick Manfred was invited to give the dedicatory address. Manfred was a friend of mine and I had the good fortune to be his guide while he was in Cedar Falls. I had long thought the two writers, Hearst and Manfred, should meet and so I was able to set up a time when that could happen. I was sure that out of such a meeting would come an illuminating exchange of ideas about literature and their own writing. I did note, however, that in anticipation of their meeting Jim seemed to be more interested in the legendary large and beat up old Cadillac that Manfred was famous for driving all over the country. After his speech at the library, Manfred and I drove down Seerley to this house. (I of course had remembered to bring a pen and paper so I could capture important bits of their conversation. The first part of their immortal conversation went like this:

Hearst: Where did you learn to write?

Manfred: I just worked at it. I don’t believe you can teach anyone to write.

Hearst: Neither do I.

So much for their analysis of literature and writing. The rest of their time together was spent talking about farming, particularly farm machinery, farm dogs, and old cars. It was a lively discussion of old time threshing machines, hay bailers, and old makes of automobiles. Some of these I had heard of: Studebaker, Packard, et al but others were completely foreign to me.

A few weeks after this event, I received a letter from Manfred thanking me for introducing him to James Hearst and in which he asked me to tell Jim that he was still positive that the Hupmobile, Model B was built in 1918.

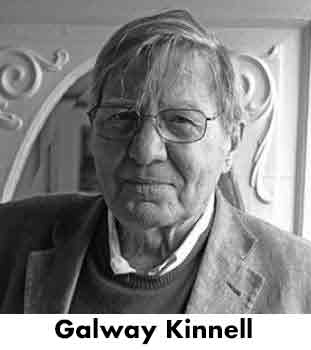

I witnessed a similar exchange between Hearst and Galway Kinnell, a poet who was here for a lecture and had expressed a desire to talk with James Hearst. Again I arranged a meeting (I was chairman of the speakers committee for the English Dept. in those days, and we had a steady stream of prominent writers and scholars coming to campus). This time also I had high hopes of hearing a revealing exchange of ideas between two important poets. Again I was disappointed. Kinnell had just moved to a farm in Illinois and was hoping to be a pork producer. He had already experienced farrowing and had looked forward to Jim’s advice (Jim wrote a number of poems about helping bring calves and shoats into the world). Kinnell wanted to know how you could help a sow give birth in a difficult situation. I remember how Jim explained the process, using his hands to illustrate. Kinnell must have read one of Jim’s several poems about playing midwife to sows in labor. “You reach down in the birth canal [he said using his hands] and push your fingers up behind the front teeth of the baby, make it into a kind of hook and then slowly pull it out.” That is all I remember from their conversation. I am fairly sure there was little talk about literature or writing.

I witnessed a similar exchange between Hearst and Galway Kinnell, a poet who was here for a lecture and had expressed a desire to talk with James Hearst. Again I arranged a meeting (I was chairman of the speakers committee for the English Dept. in those days, and we had a steady stream of prominent writers and scholars coming to campus). This time also I had high hopes of hearing a revealing exchange of ideas between two important poets. Again I was disappointed. Kinnell had just moved to a farm in Illinois and was hoping to be a pork producer. He had already experienced farrowing and had looked forward to Jim’s advice (Jim wrote a number of poems about helping bring calves and shoats into the world). Kinnell wanted to know how you could help a sow give birth in a difficult situation. I remember how Jim explained the process, using his hands to illustrate. Kinnell must have read one of Jim’s several poems about playing midwife to sows in labor. “You reach down in the birth canal [he said using his hands] and push your fingers up behind the front teeth of the baby, make it into a kind of hook and then slowly pull it out.” That is all I remember from their conversation. I am fairly sure there was little talk about literature or writing.

Jim’s practical knowledge of the ordinary, down-to-Earth matters of the world, especially farming, was something that set him apart from many literary women and men—and course it made him a remarkable, unique individual, a refreshing change from many a writer or literary scholar.

Jim enjoyed such visits from other writers, but most of them came from a much different world. Two he liked to tell about were Robert Frost and Carl Sandburg. When Frost was here to read his poems, a visit with Jim was inevitable and, of course, it required a visit to Maplehearst, the Hearst farm west of town. Jim liked to recall how impressed Frost was with the size of the land, particularly the long, long furrows of corn. But also he was entranced by the black, rich Iowa soil. Jim laughed as he recalled Frost saying, “Why that ground is so rich I could just get down on my hands and knees and skip the vegetables!”

Jim enjoyed such visits from other writers, but most of them came from a much different world. Two he liked to tell about were Robert Frost and Carl Sandburg. When Frost was here to read his poems, a visit with Jim was inevitable and, of course, it required a visit to Maplehearst, the Hearst farm west of town. Jim liked to recall how impressed Frost was with the size of the land, particularly the long, long furrows of corn. But also he was entranced by the black, rich Iowa soil. Jim laughed as he recalled Frost saying, “Why that ground is so rich I could just get down on my hands and knees and skip the vegetables!”

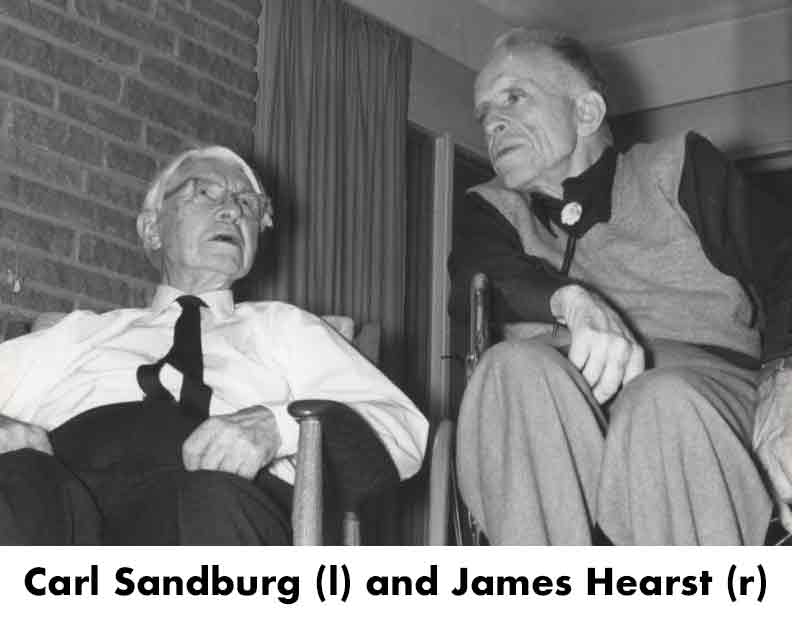

Another poet farmer who visited was Carl Sandburg. There is a nice photograph of Jim and Meryl with Sandburg in the special North American Review issue. Jim would tell of Sandburg’s discourse on the perils of literary fame (and he would imitate, as he did so, Sandburg’s nasal drawl). “Here you are, a very famous person with your name and picture in all the newspapers and magazines, and then ya still can go and get the measles.”

These exchanges between Jim and other creative souls illustrate, I believe, a unique aspect of his aesthetic. He did not talk or write much about aesthetic theory. He was an artist (and a very intelligent one), no doubt about that. But he was simply too much different from the stereotypical conception of a poet. He was an active member of the Cedar Falls Rotary Club. He helped found another club, a discussion group, the long-running Supper Club. Every month he played poker with a group of men. And finally he took up the trombone in his fifties or sixties. He took lessons and could play a pretty mean version of “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean.”

Jim was a teacher; from all accounts he was very good in the classroom. He was widely read (far more important than the degree he lacked). He was interested in his students and their problems, helpful, open, and friendly. He made it a point to know his students, and for this they liked him. I talked to three people who had been Jim’s students (one was my son) as I prepared these remarks. For years Jim taught classes in a basement room of this house, and had to go down by a motorized chair. Each of the students spoke of being awestruck when Jim made his first appearance. They were sitting quietly and suddenly Jim appeared slowly descending from the upper floor in his chair. They said it was rather spooky, certainly, but he soon broke the ice and won them over. Jim remembered his students many years later and kept up with many of them after they had graduated.

Two of his favorites had been students of mine, and the two girls cooked a dinner once for Meryl and Jim and invited me. It was a wonderful evening, one I have never forgotten. I remember well the easy affection that seemed to connect Jim and those young people. One of them has become a published writer and photographer. I wrote her recently and asked if she had anything she would like to contribute to this celebration of the Hearst Center. She responded with this photograph which she took of Jim and a marvelous excerpt from one of Jim’s letters to her (they had kept up a correspondence):

In my last semester at UNI, Spring 1970, I finally managed to get into the much-vaunted James Hearst poetry seminar held in his home. My friend Mary Ann Marchese and I walked down Seerley Boulevard every Thursday afternoon. We would leave with poetry swirling in our heads and sometimes popping, unbidden, out of our mouths. We’d have informal contests to see who could come up with obscure words and make them rhyme with something. Plethora was a challenge.

Jim (after I graduated, he wrote Don’t call me Mr. Hearst. You’re a big girl now.) made poetry come alive. I remember him reading aloud Karl Shapiro’s Auto Wreck. I could hear the ambulance and feel the wounds.

Mary Ann and I became poetry groupies. One evening we made tacos in the Hearst home for Jim and Meryl and George Day. Now that I make my home in New Mexico, I realize that they were probably horrid tacos, but nobody complained, and the conversation was good.

After graduation we became friends, and it was my great privilege to visit Jim and Meryl many times during the years before his death. During my first year of teaching, he came to Adair-Casey High School one afternoon to talk about his poetry. He, humble as ever, was relieved that the students thought he was “cool.” I hope they know how lucky they were.

I came across letters from Jim when thinking about what to write for this tribute; even his prose was poetry. His sense of humor, his generosity of spirit, come through. What a treasure these letters are. We are losing so much as we write our ephemeral emails.

“Your letter was such a pleasant surprise that the rain stopped and the sun came out. You didn’t know that you had the power, did you? Well, be careful how you use it, you might let it rain when the Methodists want a Sunday picnic, or have the sunshine when the farmers wanted rain. But we are delighted to hear from you. The only sad thing is to think how the time has gone. Your child two-and-a-half years old! I can’t believe it.”

“You know, I’ve never been a housewife nor a mother, but from where I sit, it looks like the most creative job in the whole world—maybe next to farming. But I used to cook and I had a recipe for beef stroganoff in a book of recipes by American poets. And in the fine print of our marriage contract it says that I am to have homemade bread. So Meryl, who couldn’t boil water without burning it when we were married, is now one of the best bread bakers in town.”

And so on. Those were words I needed to hear at the time—that motherhood and homemaking can be creative work too. I later went on to become a professor and a visual artist. Jim Hearst was my first model for finding fulfillment in a life of creativity. He didn’t pretend it was easy—he once said, “Writing poetry doesn’t come as a revelation. I sit there in the morning and wait for something to come, and sometimes all that comes is lunch.”

–Robbie Steinbach, April 2014.

These few sentences are quintessential Jim Hearst, humorous, affectionate, and wise.

To truly understand James Hearst, one must be aware of a reoccurring theme in his poetry and in his life. Central to his very existence was the idea of work—hard, often physical work informed his path through life and art. It made possible not only the economic success of the Hearst Farm, but it enabled Jim to survive for sixty three years after his accident.

When Jim surveyed the life that lay ahead, after his accident, he wrote, "I knew that no matter how much I read, or wrote, or helped plan, or achieved with all my mind, what really counted was the work I could do.” And he had to do it alone, for he added: “If I am going to make it I must stand on my own two feet!”

Eventually Jim was able to do the two kinds of work that were the most important to him: farm work and writing. Both were immensely satisfying. Jim saw a similarity between his physical work on the farm and his mental efforts at his desk. After they moved to this house, he wrote every day, calling it “doing his chores.” Sitting in front of the typewriter in the little cubby hole of an office by the front door he found the exertion just as demanding as driving the tractor.

The word “work” was a kind of mantra for Jim. He would exhort his creative writing classes by announcing, “You have come here to work!” Work for him was virtually a religion. Work holds you in a kind of trance or spell. “Work is a kind of addiction, it takes energy and you must put yourself into it as if you played the game for keeps.”

The religious aspect of work kept slipping into his poems as in two lines he states:

This is the temple of work

The stations of sweat, callouses

Jim was well aware of his addiction to work and he attributed it to his paternal ancestry: “The Hearsts came from New England with the disciplined attitude of people who knew that salvation does not come without work." “I don’t believe in inspiration. Writing is, for me, hard concentrated work.”

I should note that Jim’s philosophy of work evolved in his maturity. As a youngster he hated the never ending farm chores that were required of him. He was astute enough to (later) realize that his dad’s stern dedication to hard work was not shared by his mother, whose Bavarian background drew her to the joys of song and story.

Another major element in Jim Hearst’s life was love. He was a loving man. He did not wear his heart on his sleeve, he was not a sentimentalist, and he did not talk much about love. But it was very much part of him. He clearly loved his family (especially his mother), his father and his siblings. He was stricken at the death of his younger brother and wrote a simple but beautiful poem about him. Jim loved his extended family: aunts, uncles, and cousins. He was proud of them, especially perhaps his uncles and aunt who were medical doctors. Jim was hurt when he and his younger brother broke up their farm partnership over a disagreement, but afterwards he declared, “I love my brother.” Jim loved his two wives and was devoted to them. And, of course his many friends were objects of his affections.

Another major element in Jim Hearst’s life was love. He was a loving man. He did not wear his heart on his sleeve, he was not a sentimentalist, and he did not talk much about love. But it was very much part of him. He clearly loved his family (especially his mother), his father and his siblings. He was stricken at the death of his younger brother and wrote a simple but beautiful poem about him. Jim loved his extended family: aunts, uncles, and cousins. He was proud of them, especially perhaps his uncles and aunt who were medical doctors. Jim was hurt when he and his younger brother broke up their farm partnership over a disagreement, but afterwards he declared, “I love my brother.” Jim loved his two wives and was devoted to them. And, of course his many friends were objects of his affections.

I do not think it an exaggeration to say that Jim loved people, in general, the human race. Some of his poems, of course condemn or ridicule certain kinds of people but in spite of man’s cruelty and many foibles, his liberal and gentle outlook on life led him to embrace all mankind. Paul Engle put this quite succinctly in his poem about Jim: “Jim hates hate.”

Gratitude, closely allied to love, was something Jim felt deeply. His poems, autobiography, and conversations were filed with expressions of gratitude for those who helped him. He never took the invaluable assistance of doctors, nurses, orderlies, etc. for granted. The dedication of his autobiography is an eloquent expression of this as he links the idea of love with that of service:

“This book is humbly dedicated to those who in the service of love give without asking.”

You did not have to be in Jim’s company very many minutes before you were aware that he was someone who could see the comic in people and situations and in the ironies and inconsistencies of life: the human comedy. His fertile imagination could create hilarious characters and plots of high comedy.

Was James Hearst a saint? Of course not. He was human. He could be angry—as he once was with me. He could be irascible, as quite a few of his poems reveal. The voice is often cranky and profane. Jim liked salty language but used it sparingly and effectively. I don’t recall him cursing in our private conversations. But I think he enjoyed using it in verse to underscore impatience or disgust.

But when we think of Jim’s handicaps/challenges, we should consider what kind of person with what kind of temperament he might have become: easily a self-pitying complainer, sour, resentful, vengeful, rude, belligerent, self-centered. I have known people who were so affected by a serious accident or illness. Jim “might” have become like that. But he did not. I am sure there must have been terribly black thoughts, but he kept them to himself. It is almost as if he had vowed, perhaps he did, not to let his handicap and its consequences play a public part in his life. I know of only two poems which indirectly refer to that part of his life. And only once did I overhear (legitimately, he knew I was sitting there) him speak of his regret that he could not walk).

Perhaps then, this, besides his poems, is Jim’s greatest gift to us: his dignified, amiable, loving, positive character. Surely that is powerful testimony to what the human spirit can overcome and can achieve.

So you said I would be the

light of your life and the comfort

of your old age. Well, before we

reach the finish line how about

a New Year’s Eve party every week

we’ll buzz Times Square in your

little old airplane and make out

in a gondola on a Venice canal.

If we are going to build that

stairway to Paradise we better

get in shape for stair climbing,

It’s a long way up they tell me.

And how would you like a bed of furs

in an igloo on an Artic shell

for a change of pace? We gotta

make a few fast trips before comfort

wraps us in its warm wooly folds.

Let’s light the candles on a

birthday cake, the kind you can’t

blow out and let ‘em burn until

the frosting runs. I’ll throw one

slipper over my shoulder and you

drink champagne from the other.

Mrs. O’Leary’s cow burned up Chicago

don’t let us be cowed from burning up

a few streets toward the future.

If I’m to be your Light and Comfort,

let’s get in a few good licks before

the teakettle boils.